It’s a spectacularly romantic idea—returning a large swathe of western grazing land to prairie land, with bison, elk, cougars, prairie dogs, grouse, and other wildlife. That’s the goal of the American Prairie Reserve, whose owners hope to create open prairie and wildlife range extending over 3.2 million acres in northeastern Montana. “We want to restore the land to a semblance of what Lewis and Clark saw,” says Peter Geddes, vice president and chief external relations officer. ”We call it the American Serengeti.”

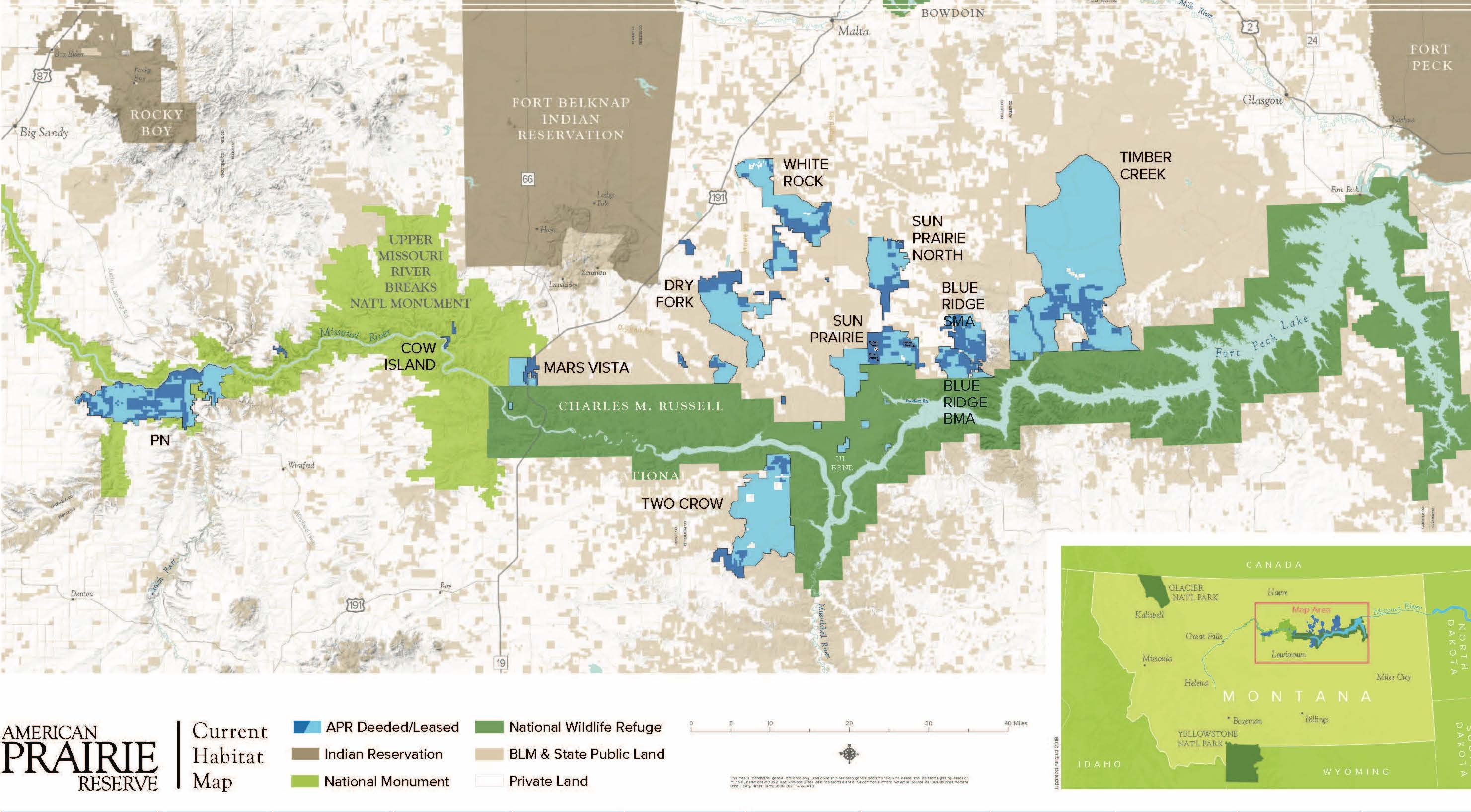

While it may not look enormous on a national map, it is. The proposed area is 5,000 square miles, close to the size of Connecticut. The area would include the 1.1 million-acre Charles Russell Wildlife Refuge, which already preserves wildlife along the Missouri River.

Many obstacles remain for the nonprofit group. It was founded in 2001, has bought 100,000 deeded acres, and has a small herd of 850 bison. Some obstacles were expected—the difficulty of working with federal agencies, suspicion and even hostility by ranchers, and the challenge of raising enough funds to buy land.

But the reserve has also caused a surprising ideological split among free-market environmentalists. Those are environmentalists, many of them economists, who argue that the private sector often protects our surroundings better than government management or regulation does. FME advocates can be found at think tanks such as PERC (the Property and Environment Research Center), FREE (the Foundation for Research on Economics and the Environment), and CEI (the Competitive Enterprise Institute).

APR is committed to buying its land from willing sellers. Its leadership recognizes that achieving the goal will take a long time—it is not trying to force quick sales. So isn’t APR a free-market-environmentalist’s dream?

APR is committed to buying its land from willing sellers. Its leadership recognizes that achieving the goal will take a long time—it is not trying to force quick sales. So isn’t APR a free-market-environmentalist’s dream?

Maybe. Maybe not.

Ownership of what was once prairie is complicated. In the early twentieth century, homesteaders settled in eastern Montana. But the region is so arid that the homesteaders could not survive on their small plots. They failed to “prove up,” and the land reverted to the federal government. The grasslands are suited to cattle grazing, however, so today the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) leases large stretches of land to ranchers. (In addition, some land is owned by the state.)

In fact, BLM leases are so connected to private ranches that when a sale occurs, the leases go to the new owner. Thus APR owns about 100,000 acres, but along with those acres came 300,000 acres of leased land. If APR ever reaches 3.2 million acres, it will be through a combination of deeded and leased land (plus the Charles Russell refuge).

This involvement with the federal government is what disturbs Terry Anderson, former executive director of PERC. “If [APR] reaches its goal of populating the ‘American Serengeti’ on lands mostly under federal jurisdiction with 10,000 bison, the privately owned bison will almost surely become public bison managed by state and federal bureaucrats,” Anderson wrote last year in the Billings Gazette. “Public lands bleed red ink and are poorly managed, and federal management of this wildlife preserve will be no different.” He also thinks that eventually APR will turn its prairie completely over to the government so it will become a gigantic park.

Anderson agrees with some of the ranchers who oppose the reserve. They consider it a “Trojan horse” that will lead to federal management and a steep decline in cattle ranching.

Not so, says APR’s Geddes (who used to work at both PERC and FREE). First, the BLM lands are already “political lands”—APR hopes to make them less so, and does not intend to give its private land to the government.

As for ranchers, says Geddes, “We have obligations to our neighbors.” APR leases back much of its land to cattle ranchers, so that 13,000 cattle graze on its acreage. The organization provides financial incentives for ranchers to make their ranches more “wildlife friendly,” and it maintains perimeter fences. It also allows limited hunting (including a few bison permits) and welcomes visitors.

Under state law APR can manage its bison as livestock. Over the longer term, however, APR managers want to change the requirements of its BLM and state leases so they can graze the bison herds as they think is best. There is a process for doing this but it is a complex one. Encouraging APR is the fact BLM is experimenting with “outcome-based grazing.” In such grazing, the BLM reduces the specific rules (such as requiring herds to be relocated season by season). Instead, it would inspect the state of the grassland and allow its lease holders to graze however they want as long as the outcome is good—the grassland is healthy.

So, is the American Prairie Reserve “an approach grounded in free market principles,” as PERC board member James Huffman wrote last year? Or is it a “Trojan horse” to create a publicly managed national park? You be the judge.

Map provided courtesy of American Prairie Reserve.

Photo provided by Gib Myers, board member of the American Prairie Reserve.

1 thought on “American Prairie Reserve: Free Market Environmentalism or “Political Land”?”