How a would-be academic discovered he was an ‘enviropreneur’

Wallace Kaufman, a regular contributor to this blog, describes his discovery of how profit-making projects can protect land.

In the late 1950s what new college student with a social conscience didn’t think the world needed a better way of motivating people than profits?

My parents had never finished high school and lived Friday to Friday paycheck. I recall sifting other people’s coal ashes to find still burnable pieces. I remember another grade school boy in our neighborhood throwing pennies, nickels, and dimes on the sidewalk for us to chase. He had the money because his parents bought soda pop from a small maker and sold it to construction crews in the first Levittown rising on the potato fields of central Long Island.

I discovered early that life was unfair. First I wished for salvation, then for alternatives.

In graduate school at Oxford, shocked by the British class system, I attended meetings of the Communist Society. When I began teaching English at UNC-Chapel Hill in the mid 1960s, my faculty peers spoke highly of socialism, and I thought, yes, I want the fairness and equality of socialism. Hippies were forming communes, but I wasn’t a hippie, and my still blue-collar mentality wasn’t ready to share my car or my tools or my wife. So, I proposed to several young professors like me that we create not a commune, but a community. They agreed that we would pool resources, find and buy a nearby piece of land, allot each a few acres, and promise to keep the place green and quiet.

I found 73 acres overlooking the lake that supplies water to Chapel Hill. Immediately the critical instincts of academics found reasons for each member to back out. They were environmentalists but not entrepreneurs. I didn’t think of myself as an entrepreneur, and if the concept of “free market environmentalist” or “enviropreneur” existed, I had never heard of it. But I became one.

I knew—or better to say I had faith—that if I could show how investors could profit by creating the kind of homestead community I was planning, I could find the money to buy enough land.

To that end I earned my real estate broker’s license and created Heartwood Realty. As a partner I recruited Elizabeth Anderson, founder of Chapel Hill’s first organic restaurant, Wildflower Kitchen. She was also the granddaughter of the writer Sherwood Anderson and obviously an entrepreneur with a social conscience.

With a graduate student friend, his father and uncle, I made a $15,000 down payment and a salary-devouring commitment to 330 acres sixteen miles south of the university. My partner had grown up selling new and used restaurant equipment with his father, and I had grown up blue- collar among people always hoping to win the Irish Sweepstakes (then the only legal lottery). We were ready to take risks, our wives more prudent. My wife Sarah and my partner’s wife Lyn had grown up in comfortable middle-class families. We named our small corporation Saralyn.

Almost as soon as our deed was recorded my partner, with Ph.D. in hand, took a job offer in New York. I wrote legal restrictions (covenants) to protect the forest and wildlife and our pristine stream. I also set aside 40 acres of commons area as a buffer along the stream. With Heartwood Realty marketing and managing sales, Saralyn financed homesteads of 5 acres and up with nothing down. Build anything you want. This was 1960s Carolina, where segregation was still in force, but Heartwood Realty advertised we would not discriminate against any race, creed, or life style. Heartwood also joined the local board of Realtors and broke the commission fixing system.

Almost as soon as our deed was recorded my partner, with Ph.D. in hand, took a job offer in New York. I wrote legal restrictions (covenants) to protect the forest and wildlife and our pristine stream. I also set aside 40 acres of commons area as a buffer along the stream. With Heartwood Realty marketing and managing sales, Saralyn financed homesteads of 5 acres and up with nothing down. Build anything you want. This was 1960s Carolina, where segregation was still in force, but Heartwood Realty advertised we would not discriminate against any race, creed, or life style. Heartwood also joined the local board of Realtors and broke the commission fixing system.

Besides selling homesteads in Saralyn, Heartwood developed a general agency business, appealing to a few, all too few, liberal faculty buying or selling their own homes and land. Support for socially responsible business was not high when the academic seller or buyer had skin in the game.

The Saralyn community was fully sold in two years and it is still a viable community—not one of the short-lived communes of transients that were popular in that era. Fifty-three years later the community still cares for its own roads and enforces its covenants. The covenants effectively assure shared core values of a real community.

With that experience, Saralyn, Inc., went on to create more rural communities with better legal craft and greater understanding of ecology. Success and the profit motive brought more investors. Some large landowners asked Heartwood Realty to create similar communities on their own land. They too were becoming enviropreneurs, although that term had yet to enter the vocabulary.

At the urging of urban planner Pearson Stewart, the new Triangle Land Conservancy recruited me to its board. Pearson hoped I could persuade the Trust to increase its funding by selling some non-essential pieces of donated land—with environmental protections, of course. (Nature Conservancy had already done this a few times in other regions.) I did not succeed in persuading the Triangle Land Conservancy to work with developers. The boards and leaders of many non-profits feel that entering the marketplace and selling land is a stain on their ideals.

By the time I left North Carolina to live in Oregon in 2001, the various communities we created covered almost 3,000 acres in the booming Research Triangle area. We had by then protected more land than any of the local conservancies or local government park planners. Our communities, ranging from 100 acres to 770 acres, are still protected islands of green with abundant wildlife amid the area’s growing spider web of highways and crowded suburbs and towns.

By the time I left North Carolina to live in Oregon in 2001, the various communities we created covered almost 3,000 acres in the booming Research Triangle area. We had by then protected more land than any of the local conservancies or local government park planners. Our communities, ranging from 100 acres to 770 acres, are still protected islands of green with abundant wildlife amid the area’s growing spider web of highways and crowded suburbs and towns.

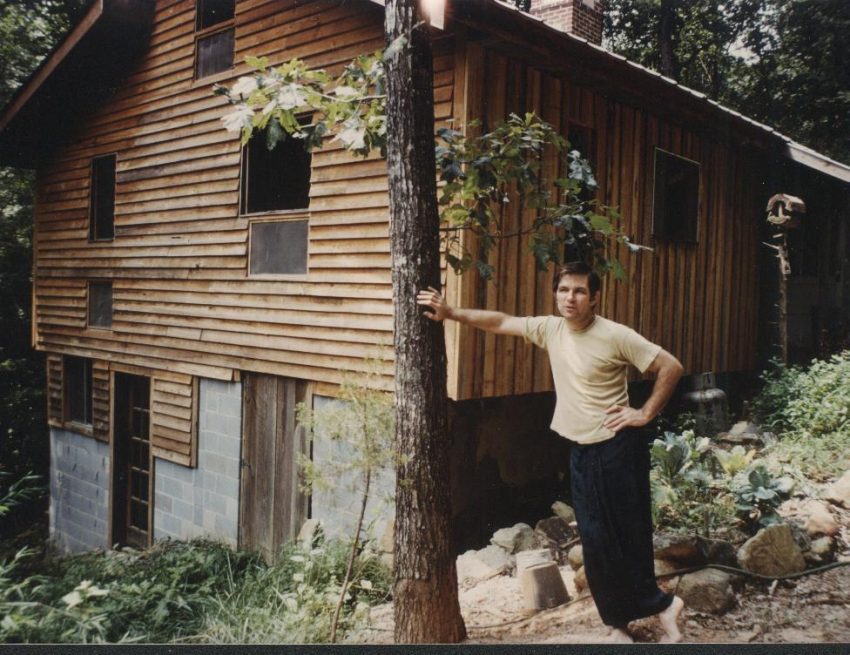

Images: Wallace Kaufman by his owner-built home in the Saralyn community. Redbud Lake, at the edge of the development. Bynum Bridge across the Haw River.