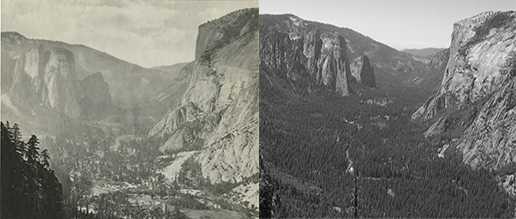

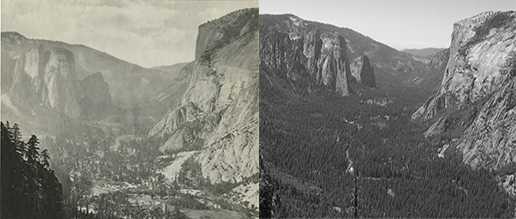

The following photographic essay illustrates the changing landscape at California’s Yosemite Valley and undermines the myth of a static “balance of nature.” The author, Shawn Regan, is vice president of research at the Property and Environment Research Center (PERC). The photograph above shows Yosemite Valley in 1899 (left) and today (right).

If it seems like wildfires are becoming larger and more destructive these days, it’s because they are. More than 10 million acres burned each year in 2015, 2017, and 2020, setting records for the modern era. The massive blazes—which often consume entire forests—threaten neighboring communities, create unhealthy air quality, and degrade the environment.

A major driver of today’s megafires is the dense fuel loads that have accumulated in many parts of the American West after a century of fire suppression. During this time, western forests have experienced large increases in tree growth and forest density. What’s emerged is a landscape that is much more vulnerable to catastrophic wildfires—and one that is in many ways unrecognizable to its early human inhabitants.

The Greatest Glory of Nature?

Long before Yosemite was set aside for protection, visitors have marveled at its granite walls, towering waterfalls, and giant trees. Carleton Watkins’ early photographs of Yosemite Valley helped attract national attention to the region.

One of Watkins’ best-known images features El Capitan, a 3,000-foot rock face extending from the valley floor. Visitors to Watkins’ spot today, however, no longer share his view. Most of the open meadows and patchy tree stands he saw have since been swallowed by the forest. When Watkins’ photograph of El Capitan was recreated in 1944, the rock formation was barely visible through the encroaching forest. Now it is entirely obstructed by trees.

Changing views from Yosemite Valley. Trees were thinned in 1944 to improve the view. Photo courtesy of the National Park Service.

Another photograph by Watkins captured Yosemite Valley from Union Point in 1866. Then, the valley was thinly scattered with trees. A recreated photograph from 2009 reveals a much different landscape. The meadows that once offered stunning vistas have been almost completely swallowed by the forest. The oak woodlands that dotted the landscape during Watkins’ visit are being replaced by a dense conifer forest.

“The inviting openness of the Sierra woods is one of their most distinguishing characteristics,” said John Muir, an early advocate of preservation. “The trees of all the species stand more or less apart in groves,” he wrote, “enabling one to find a way nearly everywhere.” In 1865, Frederick Law Olmsted’s report on Yosemite described “miles of scenery” and “the most tranquil meadows,” creating what he called “the greatest glory of nature.” Since then, the National Park Service estimates that two-thirds of Yosemite Valley’s meadowlands have been lost to the encroaching forest.

Yosemite Valley from Union Point in 1866 (left) and 2009 (right). Photo courtesy of the National Park Service.

Why has Yosemite so drastically changed? The scenery that early preservationists sought to protect was in fact a landscape largely shaped by human influence. Native Americans regularly set fire to Yosemite Valley to clear forests, maintain open meadows, and grow food. Frequent fires promoted the growth of scattered stands of black oaks, from which Indians gathered acorns. In an important sense, the tranquil meadows seen by Muir, Olmsted, and other early white visitors were as much the product of human action as they were the glory of nature.

Ecologist M. Kat Anderson explores these issues in Tending the Wild: Native American Knowledge and the Management of California’s Natural Resources. “Much of the landscape in California that so impressed early writers, photographers, and landscape painters was in fact a cultural landscape, not the wilderness they imagined,” she writes. “While they extolled the ‘natural’ qualities of the California landscape, they were really responding to its human influence.” Early explorers objected to Indians’ use of fire, a view that would later help shape federal fire suppression policy.

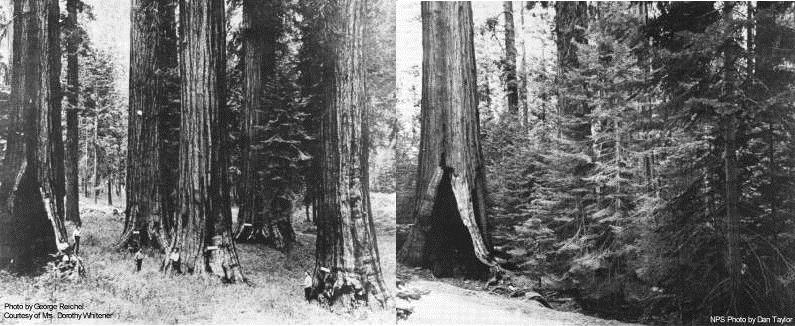

By the 1960s, however, it became clear the park’s giant sequoia trees were no longer regenerating. The sequoias, it turned out, rely on disturbances such as fire to regenerate. In the past, frequent fires kept other species under control and helped open the sequoia’s cones to scatter seeds. Without these low-intensity fires, shade-tolerant white firs began outcompeting sequoia seedlings, creating a dangerous fuel load that threatens giant sequoias by allowing fire to reach their crowns—as happened last year in nearby Sequoia National Park.

Giant sequoias of Yosemite’s Mariposa Grove in 1890 (left) and 1960 (right). Photo courtesy of the National Park Service.

It wasn’t until the 1970s that the Park Service recognized the folly of fire suppression. By then an enormous fuel load had accumulated throughout Yosemite. Many of the viewsheds that early explorers saw had vanished, and the region was becoming prone to larger, more devastating fires.

The Park Service eventually initiated a prescribed fire program to replicate Yosemite’s lost fires. For past 40 years, controlled fires burned between 12,200 and 15,600 acres each decade in Yosemite—far less than the region’s historic fire regime, in which 16,000 acres may have burned every year prior to the era of fire suppression. In 2011, the Park Service began a controversial plan to cut thousands of trees in Yosemite to restore some of the scenic vistas that have been obscured by the forest.

Yosemite Valley in 1899 (left) and today (right). Photo courtesy of the National Park Service.

If the Yosemite depicted in early photographs was the product of human influence, then to what state should it be managed today? The problem, many ecologists now say, is that there is no single correct state for an ecosystem like Yosemite. The biologist Daniel Botkin has argued that nature is not a “Kodachrome still-life” but rather “a moving picture show,” continually changing “at every scale of time and space.” Even seemingly wild places like Yosemite or Yellowstone are constantly in flux.

What’s more, the natural world cannot easily be separated from human action. In many ways the only Yosemite we’ve ever known is one created by the actions, or deliberate inactions, of people. A recent paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences makes a related point, arguing that “wilderness is an inappropriate and dehumanizing construct,” and that most of the high-value, biodiverse landscapes that preservationists seek to protect “are the historical product of, and thus require, human intervention to maintain the very values for which they are lauded.”

A dense, overcrowded forest that is unmanaged (left) compared to a forest that has been thinned and managed to reduce fire risks (right). Photo courtesy of the Salt River Project.

The challenge comes from policies that assume an inherent balance to nature apart from people. Wildfire suppression codified this static view of nature into federal forest management. Active forest management is often opposed by environmentalists, who frequently litigate to hinder such actions on federal lands. Throughout much of the West, a century’s worth of unburned fuel now stands between a single spark and a devastating megafire, putting the future of the forests and their ability to regenerate at risk.

Looking back now, Watkins’ photograph provides an important lesson: Protecting the environment is not as simple as preventing human violations on nature’s balance. It involves making tradeoffs—scenic viewpoints or dense forests—and doing so in a way that recognizes that nature is as ever-changing as the demands we place on it. How we make those tradeoffs in a world of diverse and conflicting human values should be one of the central environmental debates of our time.

Shawn Regan is the vice president of research at the Property and Environment Research Center (PERC) in Bozeman, Montana, and a former backcountry ranger for the National Park Service. His paper “Austrian Ecology: Reconciling Dynamic Economics and Ecology” appears in the Journal of Law, Economics, and Policy. He is also editor of the volume “Environmental Policy in the Anthropocene,” published by PERC.